Post an Event

Post an Event

| Benton County Republicans’ Private Fundraising Event, “Bent-on Boots and Bling” with Trey Taylor |

| Friday, September 5, 2025 at 5:00 pm |

| Featuring Trey Taylor

Music Private Event

Friday, September 5, 2025 5:00-5:30 pm VIP Reception

5:30-8:00 pm Heavy Appetizers,

Auction, Concert

Red: $750 VIP Reception

Front Row Table Sponsor

White: $500 Table Sponsor

Blue: $50 per person

Limited Seating. Get Yours Now!!!

Support Local

Dress up: Bling, Cowboy, Patriotic Benton County Republican

FUNDRAISER

www.BentonGOP.org

Get your tickets today at:

https://www.bentongop.org/event-details/benton-county-republicans-fundraiser/form

About Trey:

Trey is the youngest African American Man in Country Music History. The Denver Post wrote

"It's impossible to miss his enthusiasm. With a fondness for cowboy boots, gaudy colors and dazzling jewelry, Trey Taylor could stand toe to toe with any of the Pop, Country or even Rap

contemporaries of his generation.“ |

| Trysting Tree Golf Club, 34028 NE Electric Rd., Corvallis |

If agencies don’t hire, they get to keep the money

Editor’s note: This is the tenth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the tenth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

The Legislative Fiscal Office estimates that “[a]t any given time, roughly 10% to 15% of

authorized state positions are vacant. For example, as of August 10, 2016, a total of 4,812 state positions were vacant, representing 12% of all positions.â€

Surprisingly, the current practice of the State is to fund vacant positions, leaving the money with the agency, even if the position is not filled -- a practice that many consider to be unconstitutional.

Article III, Section 2 of the Oregon Constitution gives the Legislature all spending authority. It says, “The Legislative Assembly shall have power to establish an agency to exercise budgetary control over all executive and administrative state officers, departments, boards, commissions and agencies of the State Government.â€

With some constitutionally required exceptions, the budget process is a negotiation between the executive and legislative branches over establishing and funding priorities in spending. Some things have to be funded, because they are constitutionally required. For instance, the state has to have to have elections. But, we don’t have to have a prison system. We could just let all convicted criminals go. But we want to have prisons, so the Legislature allocates some money to the executive branch to build, staff and operate a prison system.

Most often, the Legislature gives the Executive branch -- in this case, the Department of Corrections -- broad discretion on how to run the prisons, but they only have discretion to operate a prison. Any other use of the money is unconstitutional. During the budget process the Legislature, in consultation with the Executive Branch, determined that they needed a certain level of personnel. If they fail to hire all the personnel available to them, they either find efficiencies or fall short of goals, but at the end of the day, they don't have the constitutional authority to re-allocate the resources.

Although agencies have grown accustomed to and dependent upon having this 10% to 15% buffer -- one might call it a slush fund -- some basic discipline could be imposed on agencies, and much of this money could be returned to the general fund to be properly, constitutionally allocated by the Legislature, or in harder time, cut from the budget altogether.

Savings: $500,000 million ore more biennially.

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-24 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-06 22:37:54 |

Let’s get rid of this broken agency.

Editor’s note: This is the ninth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the ninth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

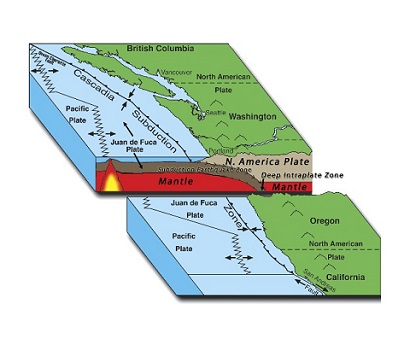

DOGAMI, as it is abbreviated, has two main departments.

The Geologic Survey and Services (GS&S) Program gathers geoscientific data and maps mineral resources and hazards. Geographic areas needing tsunami hazard mapping, landslide hazard studies, flooding hazard studies, and earthquake risk mapping have been prioritized by the agency. The information is shared with state and local policy-makers for land use planning, facility siting, building code and zoning changes, and emergency planning.

The Mineral Land Regulation and Reclamation (MLRR) Program is responsible for regulating the exploration, extraction, production, and reclamation of mineral and energy resources for the purposes of conservation and second beneficial uses of mined lands. The objectives are to conserve mineral resources and protect the environment while providing for the economic uses of the mined materials. This includes oil, natural gas, geothermal exploration, and extraction.

This agency's budget woes are so epic that the legislature would not let them have a biennial budget, instead restricting them to a single year appropriation while they get their act together.

Can the geologic survey functions be turned over to Oregon State University? They might like the work, and the agency could use a break. As far as natural resource extraction goes, the reality is that political control of this state by environmentalists means that there is very little natural resource extraction happening, so very little to regulate -- which may be the source of the agency's fiscal irresponsibility in the first place.

Savings: $4-19 million biennially, depending on how much of the agency is dissolved.

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-22 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-22 15:02:23 |

Make higher ed fund itself. It creates enough value to do so.

Editor’s note: This is the eighth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the eighth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

It's rare that an opportunity presents itself to save money while at the same time making a policy decision that makes sense.

In 2013, the State of Oregon passed a first-in-the-nation

"Pay it Forward" describing a pilot for this kind of higher education tuition plan. They way the plan works is described

in the bill itself:

"[I]n lieu of paying tuition or fees, students must sign binding contracts to pay to the State of Oregon or the institution a certain percentage of the student’s annual adjusted gross income upon graduation from the institution for a specified number of years."

The dollar amounts are dizzying. In the 2019-21 biennium, State of Oregon general and lottery fund support for four year colleges was over $1.3 billion and that represents about 18% of the budget for Oregon University programs. The state could rescind the general fund money, and back a bond to create a startup fund for pay-it-forward scholarships. Since the money gets paid back into the fund, the fund is self-sustaining -- or even expanding, if the university manages it well. Ultimately, the fund could be required to do the service on the debt that was taken on to create the fund.

There are several positive aspects of the program:

- It virtually solves the student debt problem, at least for new students who participate in the program going forward

- Universities are incentivized to get the student through their programs. Currently, Universities are incentivezed to allow students to drink beer, languish and keep paying tuition. A pay-it-forward scholar who is still attending school is tying up money that could be used for the next scholar, and the university will take more steps to help students move along.

- It will have a tendency to direct support toward students and degree programs that have value in the marketplace. Conversely, it will focus support away from programs that are tempting to students, but don't create great earning potential.

- Scholarships can be easily directed to students who are deserving based on merit, as well as need.

- Universities crave more autonomy. In 2011 the legislature moved to make Oregon's universities more accountable to their own boards and less accountable to the state This program would free them from the bonds of state funding and the strings attached to those.

This program seems to have little downside while at the same time holds great potential for revolutionizing four-year higher education in Oregon. It can also deliver some great budget cuts.

Savings: Up to $1.3 billion biennially

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-20 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-06 22:31:14 |

The State of Washington beat us to it

Editor’s note: This is the seventh in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the seventh in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Oregon law currently requires periodic emissions testing for many vehicles in the Portland and Medford areas. These tests are paid for by the vehicle owners, so the costs of doing the tests theoretically pay for themselves, though they are a drag on the economy not just in the cost of the test, but in the inconvenience borne by vehicle owners. The dollars saved by vehicle owners -- $21 in the Portland area and $10 in Medford -- will incrementally increase the economies in those regions and generate more tax dollars.

Closing the vehicle test stations might not save the state much money operationally, as the tests are self-funding, but the real estate occupied by the clean air stations certainly has some value -- probably in the millions. Sale of these locations could provide the budget with a one-time shot of cash.

Environmentalists who support the testing worry that it will lead to lower air quality, but emissions regulations on vehicles have been tightened so much that there is hardly any pollution produced.

This is what prompted the State of Washington to

end it's vehicle emissions program on January 1 of this year, 38 years after it began. The Washington State Department of Ecology stated, “Air quality in Washington is much cleaner now than when the program began in 1982. Every community currently meets all federal air quality standards. The combination of the vehicle emission testing program and advances in vehicle technology led to reduced transportation-related air pollution. We think air quality will continue to improve as newer, cleaner vehicles replace older, less-efficient models.â€

Savings: Several Million

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-18 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-06 22:27:26 |

Software makes work efficient. Let’s divert those savings.

Editor’s note: This is the sixth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the sixth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

If you've ever attended -- either in person or by video -- a meeting of the Joint Legislative Committee on Information Management and Technology, also known as the IT Committee, you've seen a familiar refrain. Whether in the early stages of asking for approval, or the later stages of reporting progress, agencies doing IT projects consistently, predictably bemoan their existing systems, heavily using the terms "COBOL", "green screen" and "mainframe". And, while they paint a dire picture of the current state, they simultaneously paint a rosy picture of how a new software system will make their agency much more efficent, productive and provide better service to the taxpayer.

Perhaps it's time we take them at their word.

These IT projects are tremendously expensive -- from the more modest ones costing tens of millions of dollars to perhaps the largest fiscal fiasco in the history of the state, Cover Oregon, which cost the taxpayers over $300 million dollars, without ever releasing a finished product. Currently, these projects are often funded with general fund money and the cost savings, efficiency and productivity promised years earlier seem to just get swallowed up in the biennial budget churn. In the end if there were any savings, they never made it out of the agency.

Here's a simple thought: What if we made every agency pay for their software project by returning the value created by the software project to the general fund. In a sense, the state would be just loaning the value to the agency. Here's how it would work:

Let's say an agency wants to embark on a $30 million software project -- a medium sized endeavor that the agency claims will make them more efficient. The legislature will loan the agency the $30 million and have it paid back over, say, a period of 15 years at the cost of $2 million per year. The Legislative Fiscal Office estimates that the cost of sustaining an employee for a year is about $125,000, which includes salary, benefits, retirement and infrastructure. That means once the software is released, they have to agree to lower their head count by 8 people (8 x $125,000 = $2 million).

There are two basic ways to draft a government budget. Budgets can be done as a current-service-level baseline budget, where the same money as the last fiscal period is allocated plus increases for inflation, plus increases for population increase, plus any possible increases for program expansion. Alternately, budgets can be done as a zero-based budget where the entire budget from previous fiscal periods are not considered and a new budget is built from scratch. As attractive as zero-based budgeting sounds, it's not possible or practical to do all the time, so Oregon has adopted a hybrid system. The savings can easily be programmed into the current service level for the agency.

The savings would be twofold. First, there would be a way to pull the savings out of the agency and back into the general fund where they can be more carefully allocated. Second, it might make agencies think twice about how badly they want to undertake an IT project and what the

actual savings might be.

One caveat: Sometimes the rationale for doing an IT project is something like compliance or increased security and there is no financial return. In these cases, the legislature could write new key performance measures to reflect outcomes based on these requirements, and forego some or all of the fiscal return. That could be the choice of the legislature and it doesn't create a problem.

Additionally, it could be argued that since only the legislature has the constitutional authority to allocate money, it's not legal for the agency to realize savings from a software project and redirect those savings back into agency programs. Any savings

must be directed back into the general fund.

As said earlier, IT projects are very expensive. The savings that could be realized by this discipline could also be very large.

Savings: Tens of Millions, each biennium

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-16 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-06 22:24:34 |

Let’s have teachers teach during the school year.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

The K-12 educational establishment is very serious about continuing education. There may be some debate about whether advanced degrees and annual continuing education is really necessary to teach third-graders, but if one accepts that that it is, it certainly needs to be done in the most efficient way.

This is perhaps a good time for a change in policy around educator continuing education. The Student Success Act, with it's dollars dedicated to continuing education and the newly formed Educator Advancement Council means that the regime of continuing education for educators is in for some changes. The low-hanging fruit of efficiency is clear: If we're going to do continuing education, let's not do it during the school year, when substitute teachers have to be employed, both at great expense and great disruption to the classroom environment. Instead, if it were required in the summer, some money could be saved.

Because of the equitable funding requirements in the Oregon Constitution, it's not usually feasable for lawmakers to put requirments on funding. However, the new Educator Advancement Council which will provide grants to regional entities who are responsible for funding and supporting professional development and other support for educators in the early learning through K-12 systems. These funds, which amount to $35.8 million for grants to regional entities for continuing education,

can be controlled by the Legislature. Some of this money will go to pay substitutes.

One might expect some push back from the teachers' unions, but a big-picture view might bring them to the table. If we don't get efficiencies like this, the cuts might come directly to education budgets.

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-14 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-06 22:18:27 |

Let’s integrate education and save some money

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Although it was controversial when it happened in 2009, the state shut down the Oregon School for the Blind and allocated proceeds from the sale of assets for the benefit of Oregon's blind students. As integrated education is increasingly -- though not universally -- regarded as beneficial for both the disabled student as well as the all of the student body, closure of the Oregon School for the Deaf seems to be not only fiscally responsible, but sound instructional policy.

At the beginning of the 2018-19 school year, OSD was serving 117 students with 62, or 53%, of the students in the day program and the remaining 55 students residing on the campus during the school year. At about $19 million per biennium, that's over $81,000 per student annually. It seems like they could be both better served and more efficiently served by local school districts partnering with their local Education Service Districts.

Though the budget for the agency is over $19 million, shuttering the institution certainly wouldn't return all that money back to the general fund. These students still have extraordinary needs and that costs money -- though probably not $81,000 per year. The 52 acre campus could generate much revenue at sale.

Savings: $3 million one-time sale of assets, plus $5-10 million biennially

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-12 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-01 21:31:10 |

The taxpayers pay more for each ride than the rider does.

Editor’s note: This is the third in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the third in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

For years, fiscal conservatives in Oregon have railed (no pun intended) against inter-city passenger rail in Oregon. This isn't light rail, like you find in Portland, nor is is Amtrak, which has grey cars with the red and blue logo running north and south where it can squeeze on on freight rail tracks. No, this is inter-city passenger rail and the State of Oregon owns two train sets called Amtrak Cascades, which are kind of cream colored with a maroon and green swoosh on them. It's meant to carry passengers between cities, hence, intercity passenger rail.

These trains run from Eugene to Portland several times a day, and have been criticized for being highly subsidized.

Ridership is flat -- a fact that may be driven by the not-so-great

on-time performance of the system. In its defense, since freight trains get priority on the use of the rails, the Amtrak Cascades lines get pulled over to let freight through, but this single fact means that the train cannot be depended upon as a means of commuting -- at least not to a job where you are expected to show up on time. Ridership tends to be limited to Portland/Salem/Eugene shopping tourism, as far as that can go.

After the 2017 Transportation Package passed, Democrats made the general fund rail subsidy go away and turned it into an

other funds allocation. The source of this money is a little bit cryptic and needs explanation. Remember, that general fund allocations are the first ones that the budget cutters go after -- especially if they aren't highly necessary core services, like public safety or indigent health care. For years, the subsidy to intercity passenger rail was listed as a general fund items and the budget dogs barked incessantly at it. More recently, the source of funds was changed to be from the "Lawnmower Fund" -- an "other fund" source -- possibly in an attempt to get the budget dogs to back off.

What is the "Lawnmower Fund"? This is more formally known as the Transportation Operating Fund. In Oregon, the state gas tax, which is constitutionally dediacated to the Highway Fund is collected at the rate of $0.36 per gallon of gasoline or diesel. Except, if you're not going to use the gasoline or diesel to operate a vehicle on the highway, you can fill out some paperwork and not pay the tax. Most people don't know this, or even if they do know, they don't care to bother with the paperwork to save less than a buck, so they just pay the tax on their can of lawnmower gas. The state estimates the amount of overpayment on this tax and diverts it from the Highway Fund and into the Transportation Operating Fund, which the Legislature can use as a slush fund for whatever it wants.

In this case, the money was slushed into Amtrak Cascades to the tune of $10 million. A re-thinking of this program could put that money in service of a better use. The Oregon Department of Transportation reports ridership for 2019 at 103,185 riders. Dividing $10 million by that number means that each ride is subsidized to the tune of about $97 per ride, which is far more than the cost of a ticket.

Savings: $10 million biennially

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-10 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-01 21:25:50 |

We love libraries. but not to the tune of $10 million

Editor’s note: This is the second in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Not many people know about the Oregon State Library. One of the strategic goals of the Oregon State Library, as expressed by the agency in it's

budget presentation during the 2019 session, is to "Build awareness of the State Library." Some might say, that if you have a state agency that no one is aware of, maybe it doesn't need to exist -- especially if it is tapping over $10 million dollars from the state general fund.

At first blush, cutting the Orgon State Library might seem to be mean-spirited. Who didn't grow up spending time in the neighborhood library? To make matters worse, the Oregon State Library sponsors the very popular Ready to Read program which funds local libraries' programs to read to younger children. Still worse, it runs the program for persons with "print disabilities" which means Talking Books and Braille services. These facts might be a demagogue's dream, but they fade on closer inspection.

First, the State Library doesn't have much to do with the Ready to Read program. It merely administers the grants, and this could be done by any other agency. The programs for print disabled persons serves fewer and fewer people each year and soon will have fewer than 1,000 persons served. Most younger persons who are print disabled meet their needs through electronic means. Finally, the need for libraries as a place where books are checked out has effectively been replaced by Google. If that makes you sad, very well. If you think $10 million elsewhere in the budget will make you feel better -- or even returned to the taxpayers -- you might find a better case for that.

If you're a millenial you might want to pay a visit to the Oregon State Library. They have a card catalog room. If you don't know what a card catalog is or how to use it, you might want to get over there and check it out (no pun intended). Otherwise you might never see one.

The State Library gets about $6 million directly from the state general fund and about $4 million from assesments on other agencies, which is essentially general fund money.

Savings: $10 million biennially

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-08 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-01 21:21:50 |

An in-depth look at the State budget

Editor’s note: This is the first in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

This article is the first in a series of articles on the budget of the State of Oregon, with a specific focus on how it can be cut is such a way that minimizes the impact on taxpayers. Oregon does budgets on a two-year cycle, called a biennium, which means that spending and revenue are projected for two years. If you'd like to, you can

read the entire 546 page budget for the 2019-21 biennium. If you are busy and don't really have the time, you can read the

2019-21 Budget Highlights which is only 207 pages long. Spoiler alert: The final tally is $85.8 Billion.

The primary source for information on the budget is the

Oregon Legislative Fiscal Office, which works for the legislature to craft the budget. Working out of the limelight, they do the work of listening to the various elected officials and weaving their priorities into the budget (actually many budgets) that the legislature votes on.

This series is focused on budget cuts, and some cuts make more sense than others -- not because of where the money is spent -- but because of where the money comes from. For instance, about $22.4 Billion is the General Fund, which, for the most part, comes from income taxes paid by individuals and corportations. Cuts from these funds would make possible tax cuts or other spending possibilities, as decided by the legislature. This is where the real action is. As a side note, even though much of lottery funds are dedicated, lottery funds most always displace spending that would be general fund spending if the lottery funds were not available. Because of that, lottery funds are viewed as similar to general funds.

A slightly larger chunk of the budget is money from the Federal Government. It may be easy to say, “Let’s cut welfare,†but at the end of the day, most welfare -- though administered by the state -- is paid for by the Federal Government. It's surely true that these are still taxpayer dollars and that the money ultimately comes proportionally from Oregonians, or -- because the feds are so deep in debt -- from Oregonian’s grandkids, but cuts to federally funded programs merely create space for the feds to fund another program in another state.

The last kind of revenue is called "Other funds" and it’s not just an "everything that doesn’t fit" category. It has an actual meaning. It’s all the money that the state receives in the form of fees, fines and sales. In a perfect world, the state would have all people who use state services pay for those services, and the state does this as far as it is able and fair. So, if you want to camp in a state park, the state charges you a fee for that to cover the costs of maintenance. Lately, state parks have been booking up earlier and earlier, and if the state of Oregon was a for-profit entity, they would keep increasing the price, as the demand went up. As a state steward of all the resources for all Oregonians, the state has determined that these resources should be available to all Oregonians, not just the rich. That makes some sense, though now they are only available to those who click the fastest.

In other ways, the state tries to get payment from those who use the services. If you drive a car, you use the roads in the state and you’ll probably eventually buy gas, which is taxed and constitutionally dedicated to roads. If you walk, you don't pay that tax. The same is true if you buy a fishing license, rent public housing, or many other ways to use state services that are not availble to all.

Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to charge people for the services they are provided. Some of the Oregon Health Plan, for instance, is funded by the state general fund. We can’t charge poor people a health care premium that they are unable to afford. And good luck trying to get inmates in the Oregon State Correctional Institutions to pay for their room and board, though they are involved in some economic activities that bring money into the state. You guessed it. This money is called "other funds."

In the coming days, this series will explore in detail possible cuts to Oregon's budget. This is a questions that will arise during upcoming sessions and long into the future. This is a conversation that is sometimes obscure, sometimes controversial, and sometimes in the tall weeds, but is always necessary.

--Staff Reports| Post Date: 2020-07-06 08:00:00 | Last Update: 2020-07-06 08:28:05 |

Read More Articles

Editor’s note: This is the tenth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the tenth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the ninth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the ninth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the eighth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the eighth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the seventh in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the seventh in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the sixth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the sixth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the third in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the third in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a multi-part series on the budget for the State of Oregon and where possible efficiencies can be found.